Wake Photography 101: Part 1 – The Basics

Last year I posted an article to the Alliance website that gave a general guideline to photographing wakeboarding and wakeskating. Now that our 2009 Photo Annual issue of the magazine has hit stands and mailboxes, and that this site is starting to host some Photo of the Week contests; I thought now might be a good time to bring that article back, optimized for the new website and with some fresh photos.

We’ve broken the article up into a handful of different pieces so as not to overload you guys on photo-dork tech info. Part 1 just talks about the basic principles of photography and how some of them can apply to wakeboarding. Read on and hopefully you will find something useful to you. Check back tomorrow and we’ll be discussing different angles and techniques you can shoot wakeboarding and wakeskating from.

Nothing gets me more excited than seeing somebody pick up a camera and get the “photo bug.” I got bit a long time ago and am still “sick” with it (and am sure to remain that way for a long, long time…). I’ve learned a lot since my first photo was published in Alliance back in 2002, so I figured it would be good to write a sort of “how to” article with some fresh pictures and some explanations/ideas that will hopefully continue to help others when it comes to getting behind the camera while out on the boat. If you’re interested in what I do when I’m out at a shoot, what I look for in a submission from other photographers, or what I think you can do to take better wakeboarding photos; read on. If not, the videos page usually has something new every couple of days…

Note: this article is designed for readers using an SLR camera — one with interchangeable lenses. A basic understanding of how a camera works is helpful, but not necessary.

I love photography. A lot. One of my guilty pleasures occurs whenever a new magazine arrives in the mail; I sit down and pour over the photographs, trying to figure out how the photographers behind each image made it happen. I did it as a subscriber to wakeboarding magazines as a kid and I still do it today, with publications from this sport and others. I’ve only surfed a handful of times in my entire life, but I subscribe to several magazines because I love the photography. Same thing with snowboarding – I’ve never done it (I ski… shakas for two-plankers keeping it real on the slopes, bros!), but I subscribe to some magazines to get my necessary quota of cool photo intake and acquire some always-needed inspiration. As a kid back in the day looking at all the great wakeboarding photographs in the magazines from the likes of Tom King, Doug Dukane, Trey Tomsik, Ricky Ephrom, Kelly Kingman and others, I used to sit there and wonder, “How the hell did they get that photo? And why can’t I do that?”

Eventually I got inspired enough to pick up a camera and start shooting the sport myself. And after a lot of time and luck, I’m here to tell you that you can do that (with practice and a general knowledge of photography), and hopefully this article will help you learn how.

Basic Photography

Before we delve into combining photography with wakeboarding, we’ve got to start with some basic photography lessons.

Photography is literally the capturing and recording of light onto a light sensitive plane of film (or now digital sensors). There are two basic functions that affect/control how much light hits the plane: shutter speed and aperture.

1. Shutter Speed. The faster the shutter closes the less light will hit the film. If the shutter is slower, it is open longer and allows more light to come through.

2. Aperture. A lens’s aperture is much like the pupil of your eye. The smaller the hole, the less light that will hit the film. The size of an aperture is referred to as an f-number or f-stop. You will frequently see labels like f1.4, f5.6, and f16 — these are all different f-stops. Out of these three apertures, f1.4 would allow the most light, f16 the least.

A second, and very, very important feature of a lens’s aperture is depth of field. The depth of field of a picture is the amount of the frame in focus or sharp. An f-stop of 1.4 has an extremely shallow depth of field, meaning only what you focus on will be sharp, the rest of the frame will be soft and out of focus. A picture taken at f16 will have a much deeper depth of field, meaning what you focus on, as well as much of the foreground and background will appear sharp. Depth of field is also affected by what lens you choose and how far you are away from the subject. The shorter (more wide angle) the focal length (zoom) of the lens, the greater the depth of field. The greater the distance from your camera to the subject, the greater the depth of field, as well. So if you were really close to your subject with a long lens and shooting at f2.8, you would have a very, very shallow depth of field. But if you were far away from your subject with a wide lens and shooting at f16, you would have a very, very deep depth of field. For example pictures demonstrating how depth of field can be controlled, scroll to the end of the gallery in this article.

A shallow depth of field helps keep the background soft so the subject can really pop in the frame. Harley Clifford at Brostock '09. ISO 200, 1/1250th of a sec. @ f5.6

*Terminology note: Aperture and f-stops can be very confusing at first and hard to understand the terminology. Here is an overview to help.

On early cameras the aperture was adjusted by individual metal “stop” plates that had holes of different diameters. The term “stop” is still used to refer to aperture size, and a lens is said to be “stopped down” when the size of the aperture is decreased. The standardized, full stop of series numbers on the f-stop scale runs as follows: f/1, f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, f/8, f/11, f/16, f/22, f/32, f/45, f/64. Many lenses and cameras have the option to change f-stops in full stops, half stops and third stops (e.g. f2.8, f3.2, f3.5, f4). The largest of these, f/1, allows the most light. Each f-stop after that admits half the light of the previous one. A lens with a larger aperture is said to be “faster.” A lens that opens up to f1.4 is said to be faster than one that can only open up to f2.8. On many lenses there is a “floating” aperture. For example, a common lens in the consumer market with a floating aperture is the 75-300mm f4.5-5.6. This means that at 75mm the lens can open up to f4.5, but if zoomed out to 300mm, the lens can only open up to f5.6 — losing two thirds stops of light.

The third thing affected by the light is the film. Film speeds, known as ISO, are what determine your shutter speed and aperture. Slower film (e.g. ISO 100) requires more light to be properly exposed, whereas faster film (e.g. ISO 3200) requires much less. To be specific ISO 3200 film requires five less stops of light than ISO 100 film. The full stops of film are 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600, 3200, but many modern cameras (including digital) can be set at half or third stops for film speed. Slower speed films (100 and 200) would be used in high light situations, while faster speed films would be used in lower light situations. Higher speed films are also grainier than slower speed films, especially when images are blown up into large prints/files.

*Terminology note: Stops. A “stop” in camera talk is basically a change in setting for one of the three items above: shutter speed, aperture, and film speed. A full stop in shutter speed is 1/500 sec to 1/1000 sec. A full stop in aperture is f1.4 to f2.8. A full stop in film speed is ISO 100 to ISO 200. Each of these can be referred to in full, half or third stops. For example, “I opened my aperture half a stop,” or “I bumped up the shutter speed two stops.”

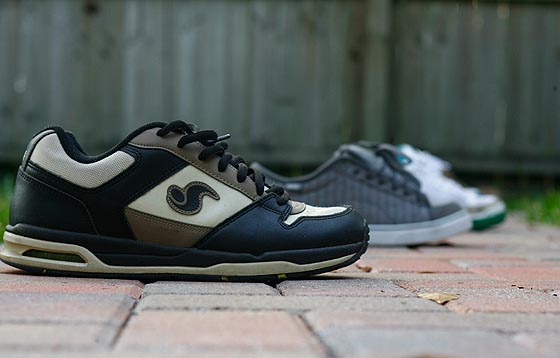

70mm focal length, f2.8. Notice the shallow depth of field. One shoe is in focus and the rest are gradually more and more out of focus. This creates separation between the subject and the rest of the photo.

70mm focal length, f16. Notice the background and foreground even more in focus from the point that's in focus.

Applying it to Wakeboarding

So we’ve established a rough foundation for understanding photography and how to control the light coming into our camera. Let’s now take those shutter speeds, f-stops, film speeds, and the depth of field and apply it to some wakeboarding action.

Time of day: If you want your pictures to look like the ones in the magazines you’ve got to shoot at the same time the pros do. There are two times during the day to get good light: dawn and dusk. The period right after sunrise and right before sunset are referred to as the “golden hours” of photography. When the sun is low on the horizon the light is very warm, and because it is coming from the side (as opposed to straight above), it fills in the picture nicely. During the afternoons when the sun is high in the sky pictures can be very unflattering. The light source is now coming from above and casting harsh shadows across the rider’s face (and everything else), often causing the picture to appear flat because light isn’t filling the subjects as well.

Shooting when the light is too high will leave too many shadows on the rider and the image will have less depth. Bob Sichel on the '08 Coming Up trip to Lake McClure, CA. ISO 200, 1/1000th of a sec. @ f5.6

Shooting when the sun is low on the horizon will fill the rider in nicely and add depth to an image. Trevor Hansen on Lake Oroville, CA. ISO 200, 1/1000th of a sec. @ f5.6

Camera settings: Of course you are going to want the best looking picture possible, this starts with the film. With wakeboarding, photographers almost always use ISO 100 or 200 film – the colors are rich and the film is less grainy. These film speeds are slower so, as we now know, they require more light to be properly exposed. To do this we will stop our aperture down anywhere from f2.8 to f4 or 5.6. This is convenient because it creates a shallow depth of field, separating the in-focus rider away from the out-of-focus background. Now, because we are allowing in so much light with our large aperture, we are going to need to compensate by using a fast shutter speed, which, again is convenient because wakeboarding is a fast-action sport and you will normally want a high shutter speed to freeze the rider.

The typical setting in my camera while doing a photo shoot is usually around: ISO 100-200, f4-f5.6, 1/1000 – 1/2000 sec. This is a good place to start while starting out on wakeboarding photography. Of course, this is providing that you have good light conditions (no clouds, etc).

One of the most important things when adjusting your camera’s settings is the light meter. Every camera has a light meter built into it and most are visible inside the viewfinder. The light meter will tell you if the settings of your camera are underexposed, overexposed, or correct for the subject you are shooting. Learn how to read your light meter! Make sure that what your light meter is reading, however, is what you want to turn out in the picture. If the meter is reading off of a shadow over the water, you will slow your camera down because the meter will think it is dark. The shadow will be properly exposed and turn out quite nicely in the picture, but everything else will be blown out. If you meter off a well lit hillside and speed your settings up, the hillside will be nicely exposed, but everything else (including your subject) will be quite dark.

Framing the picture: One of the most important and underrated aspects of photography is the framing/composition. You might have gotten a great action shot of the greatest rider doing one of the greatest tricks, but if your composition sucks, then the photo isn’t going to look very good. If you can combine good light with a unique angle and compose the frame well, you will have a gorgeous photograph. Many photographers will tell you about the rule of thirds. The rule of thirds is designed to keep the subject you are shooting out of the middle of the frame, where it can seem stagnant and boring. Split the frame into thirds on both vertical and horizontal lines and you will have something that looks like a Tic-Tac-Toe game.

By using the rule of thirds, especially when the rider is not taking up much of the frame, the picture becomes much more dynamic. For an example of the Rule of Thirds, see the image of Parks Bonifay taken out on Tampa Bay. Imagine how boring this photo would look if I had put Parks right in the middle of the frame when I fired my camera — there would be a ton of sky, very little water, and almost no boat in the frame. Now I know what you-re saying, “How can I use the rule of thirds if the auto-focus of my camera is right in the middle and the rider is off in a corner?” Here’s the answer: manual focus. I know it can be tough, but with practice you will get used to it and your photos will start to look amazing. If you absolutely have to use auto-focus, many cameras have different spots you can select to be the auto-focus sensor. Try using one off to the side or a corner rather than right in the middle.

Wakeboarding is a vertical sport, so it is often good to keep some perspective in the picture that way the reader can see how high the rider is going. To do this, whether you’re shooting vertically or horizontally, you’re going to want to keep the rider towards the top of the frame. Of course this doesn’t mean you have to use the rule of thirds in every photo you take, or that you have to keep perspective of the water every time the rider you’re shooting jumps. Fortunately, wakeboarding is an action sport and intense action can often times still make for a great photo, even when it might seem compositionally bland. Keep in mind these are just suggestions. One photographer might compose a photograph differently from another as they might see a situation differently or have a different vision of what they want the final outcome to look like — maybe shooting vertically instead of horizontally, etc. This is the great thing about photography. No two photographers are the same – each has his/her own style. Much like wakeboarders have their own individual riding style, photographers have their own vision and shooting style. Don’t be afraid to experiment and try new things. The next few suggestions might help you with this.

It's often good to show the water in wakeboarding photography to give the photo perspective, but it isn't always required. Ben Greenwood hitting a double up. ISO 200, 1/1000th of a sec. @ f5.6

Not all photos have to follow the rule of thirds or keep perspective. Be creative and try different things.

- This photo breaks a lot of composition “rules”, but still looks cool because of the light, action and water. Clay Fletcher in Orlando. ISO 200, 1/1000th of a sec. @ f10

To see the best photos the sports had to offer in 2009, head to your local pro shop and pick up a copy of the Dec/Jan issue (10.1) of Alliance, or subscribe here: https://alliancewake.com/subscribe/

For information about entering an Alliance Photo Battle on the website and the opportunity to win some sweet schwag, check here: https://alliancewake.com/wake/the-alliance-photo-battle/

December 1, 2009

Garrett, you are so smart and good at taking pictures. 🙂